The Impact of Legacy Giving

How a bequest allowed the Music Academy

to have a permanent home

Helen Marso

Helen Marso

Helen Marso was an unassuming woman, a person who was generous to friends

and family in need. In 1950, she was nearing 70 years old and had been

employed by the Jefferson family for decades. She had never been fond of

fancy clothing, nor was she overly interested in material possessions. She

never married or had any children.

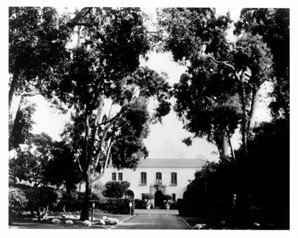

When Mary Jefferson passed away in June of 1950, though, Helen Marso

suddenly found herself in possession of a fortune. While the Jeffersons had

willed the bulk of their estate to their niece, Alice Wetmore Brann, their

longtime assistant was not left empty handed. The $180,000 bequeathed to

Marso was a massive sum at the time, the equivalent to nearly $2 million in

today's money. One of Marso's first acts was to purchase the estate,

Miraflores, where she'd lived with the Jeffersons for years. She had no

intention of keeping the 23-acre property, however, and instead offered it

to the Music Academy. Her only stipulations were that John and Mary

Jefferson be recognized in some way and that the property forever remain a

conservatory for training musicians.

The Music Academy board at the time was deep in the planning for the fifth annual Summer School and Festival. The long-term viability of the organization was still very much uncertain, though, in large part because it had no permanent facilities of any kind. The Cate School in Carpinteria had proved a wonderful location for the first few festivals, but as the Academy grew and expanded it needed a more suitable arrangement. Marso's proposed gift arrived just in the nick of time. Helen Marso's magnanimous act certainly solved the problem of a permanent home for the young institution, but it also created others. How would the Music Academy handle the upkeep? The taxes and money associated with maintaining the property? And Alice Wetmore Brann was planning to sell the Jeffersons' remaining belongings, so how would the Academy afford to furnish the house?

After a lengthy discussion, the board decided to accept the gift of Miraflores. Alice Wetmore Brann did, indeed, sell the furniture and belongings still in the house, but she also had her eye on something else that wasn't technically hers: two beautiful chandeliers that hung in the home's formal living room. So, she struck a bargain with the Music Academy. She took possession of the chandeliers in exchange for a $1,000 donation toward the purchase of new furniture and an agreement to provide "adequate lighting" for the room. Later that year, in April, she also deeded a small amount of beachside property to the Academy and offered to take care of the estate taxes.

The Music Academy officially accepted "with thanks" Helen Marso's gift

during a special meeting of the board on April 11, 1951. The Academy's

offices were moved to Miraflores on June 1. Although the property was not

ready in time for the 1951 Summer Festival, the public was invited to an

open house in August that featured a performance by the Academy's new

chorus. The many full-sized bedrooms in the home were adapted into offices

and faculty teaching studios, while other rooms became practice spaces. The

larger rooms in the house were easily transitioned into rehearsal spaces

and concert venues; the formal living room-the one from the Great

Chandelier Bargain-became the central space. Today it is known as Lehmann

Hall.

Seventy-five years later, it is clear that accepting Helen Marso's gift of

Miraflores was a masterstroke on the part of the board. More than that, it

was the creativity of a donor, the generosity of a legacy gift, and the

dedication of a group of volunteers that forever transformed the fortunes

and future of the Academy.